|

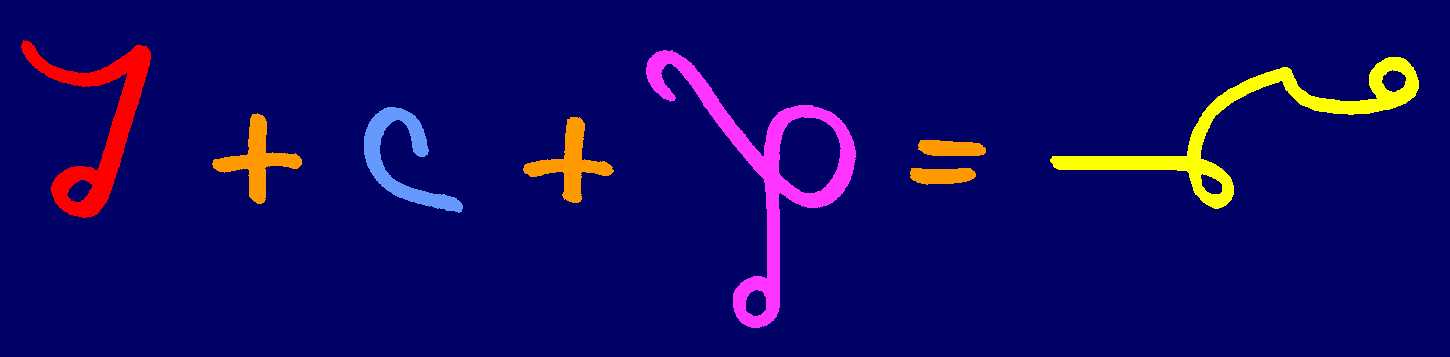

Intelligence + effort +

persistence = excellence

The theory

pages provide a compact and detailed reference source and are

designed to give more information than the average course book

provides. Their best use is for review and revision, after your

basic instruction is completed. I would encourage complete

beginners, who have no prior knowledge of Pitman's Shorthand, to

concentrate their primary efforts on the more simplified information

in their instruction book.

Course books do not go into minute detail, nor should they – the

student would get "theory indigestion" and probably give up, and the

textbook and course fee would double in size and cost. They, and

teachers, rightly present the information piecemeal, in a form much

more easily learned, and so the information here does not replace

that in any way.

Where suggested outlines are offered,

most of these do have the root word in the dictionary (large 1974

edition), and, where not, the suggestion is based on an existing

outline. I have not marked up every occasion where the outline was

not in the dictionary, as some are so basic that no note is

necessary.

The Rules

I have included explanations so that outline

decisions are not felt to be frustratingly arbitrary, but are seen

as honed for speed and reliability under pressure. I have given as

many examples as possible, to give you plenty of material to

practise with, and you can easily work out how similar words would

be written.

The basic rules

of the system cover most outlines, but there will always be

combinations of strokes that produce awkward outlines, or ones that

would not stand up to being written rapidly. Over the time since its

creation, experience has thrown up words that are better written "in

the exception" and consequently their departure from the general

rule has to be described. If only one word behaves like this, it is

called an exception; if there are several words, then their

behaviour gets to be enshrined as a subsidiary rule. Should a new

similar word arise, then there is a rule in place to deal with it.

It is just like

speaking English, people use words and sentences that are easy and

convenient, and they will use irregular pronunciations, verbs and

plurals without a second thought for the extra pages that

grammarians will have to write. Shorthand becomes the same as your

skill increases and new words (i.e. ones whose outlines you do not

know) are recognised as being based on ones

that you already know. This is the only way to write unfamiliar words

during dictation, with thoughts of theory kept for more leisurely

hours when you are correcting your shorthand.

In study hours, it is sometimes helpful to

construct that unknown outline, to exercise your theory skills.

Finding out for yourself what does and doesn't work prevents you

from feeling that outlines have been chosen arbitrarily. Sometimes

one stroke joins very well after another, and then the third stroke

cannot be joined at all, and you must backtrack on your choice. It

is great encourager when you have worked out the correct outline,

and that adds to your shorthand confidence. All this has, of course,

already been done by countless contributors and revisers over very

many years, not least by Sir Isaac Pitman himself who spent his

entire adult life considering all the outline possibilities. All

this effort and expertise is close to hand and at your fingertips in

the shorthand dictionary.

If the rules

were kept few and tidy, the shorthand itself would suffer from

unclear, straggling or hard-to-write outlines that would deteriorate

at speed. There is one overriding rule that covers all the "rule

breaking" – the outlines must conform to:

-

Facility

– easy to

write

-

Legibility

– easy to read

-

Lineality

–

maintaining horizontal writing, not invading the lines above or

below

To quote Sir

Isaac Pitman himself from his Manual of Phonography of 1852

para 91:

"For any given word, the writer

should choose that form which is most easily and rapidly written,

and is at the same time distinct. The briefest outline to the eye is

not necessarily the most expeditious to the hand. The student will

insensibly* acquire a knowledge of the best forms by practice and

observation, and he will derive much assistance from perusing the

"Phonographic Correspondent," and other phonetic shorthand

publications. In deciding between two or more outlines for any word,

he should adopt that which unites the greatest degree of facility,

with a capability of intelligible vocalization."

*"insensibly" here is an older use of

the word, meaning "imperceptibly, unconsciously"

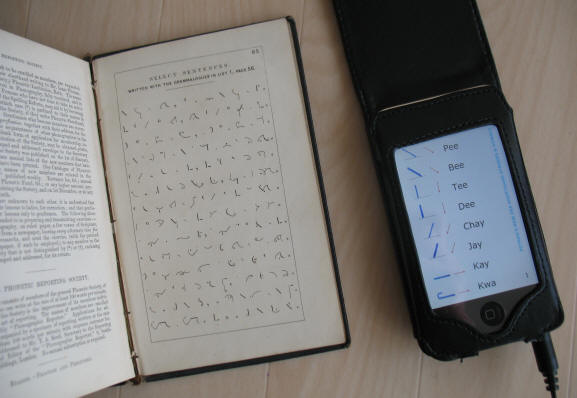

From I-SAAC to I-POD in 158

years!

Information on various instruction books is now on page

Shorthand Books

New Era

I do not believe New Era is

particularly difficult to learn, if you enjoy your learning. It is beneficial to learn the theory from your instruction book as

quickly as your time available allows (without sacrificing

thoroughness and practising of matter learned) in order to reduce

the time spent suffering the frustration of only being able to write

some words and not others. The theory on this website is best used

for subsequent review and revision, or filling in points that you

did not understand from the textbook if you do not have a teacher to

ask.

I started office shorthand work

with a speed of 120 wpm and I feel this is a good figure to aim for,

so that you are not struggling all the time, and can maintain

reasonably neat shorthand rather than an embarrassed sprawl. All

speeds up to that are highly commendable, as they will have been

gained through hard (and enjoyable) work, but in real life people

seldom speak at less than 100 wpm. Any slowness in the overall speed

comes from the pauses, rather than the laboured, even dictation that

shorthand learners become accustomed to. It is good to practise fast

bursts, with pauses after, which is more lifelike. Getting too far behind

the speaker takes away all enjoyment of using your hard-won and

valuable skill, and you might be called upon to read back

immediately rather than escape to your desk to mull over the

outlines!

Secretarial courses of shorthand and typewriting at the time I

learned them (1970's) were considered more lowly manual skills for

those less able in academic terms. There was not the slightest

perception that it was difficult, just something utterly basic to be

learned by those "destined" for the lowlier jobs. My shorthand

classmates arrived at college with this attitude already in place,

unaware that they were doing such a disservice to their own

intelligence and capabilities. However, I believe everyone's

self-esteem increased rapidly throughout the college year. Having

gained exam passes for both the "higher" (academic) and "lower"

(commercial) subjects, I can confirm that I found the "lower"

definitely more enjoyable, practical and useful throughout life.

(More on college shorthand experiences on my

About page).

Shorthand is only seen as

difficult nowadays because it is less well-known and the assumption

is often made that a rare skill has to be a difficult one. It is

rare only because it is not requested by employers as it was in

previous years. That rarity could be an advantage if you can list

shorthand on your CV, but there is also the necessity to make known

your possession of this skill. A computer desktop picture of some

shorthand outlines may be in order – see the

JPGs for Ipod, use part of

the Flying

Fingers poster JPG, or indeed any shorthand JPG on this website.

On my course we learned all the

theory in the first term from September to December and the other

two terms were spent on speed practice and gearing up to various

shorthand exams. This course included other commercial subjects, so

shorthand was not taking 100% of study time. Our successes came from maintaining our interest and enthusiasm throughout that year, and of

course our patient and kindly shorthand teacher who encouraged

everyone equally. Often interest grows as one learns a subject,

novelty turns into familiarity, and then into usefulness.

Shorthand requires precision and exactitude to be done well, and

you cannot "waffle" your way through exam answers or the

production of verbatim transcripts. It is better to study and

prepare well, rather than find out the hard way that employers are

not amused by errors or omissions in the transcript or report. It is a

skill that is a source of great

satisfaction once one has learned it to a useful level, even

if exams are never undertaken.

Whatever

shorthand you use, it is a worthy achievement, both in the skill

gained and the bravery of facing unknown dictation at unknown

speeds, totally unruffled and with the confidence that you can get

it all and transcribe correctly. Your first public arena for using

this skill may be via the telephone message pad, but rest assured it will not go unnoticed for long.

Pitman 2000

This is a simplified version of

New Era. It was introduced in 1971 as "Pitman Shorterhand", which

was dropped soon after in favour of the name Pitman 2000. It has

slightly fewer rules and omission of many short forms

and contractions. The purpose was not to "improve" New Era but to

make shorthand easier and quicker to

learn for those who do not aspire to the highest speeds. Against the

advantage of easier learning, there is the disadvantage that some

outlines are longer, and some joins between strokes are allowed that

New Era discourages as being not so easy to form, or less reliable under

the stress of speed. At lower speeds, this may not be an issue, and

confidence in the formation of the outline may possibly make up for

this. It was not intended to replace New Era, but was aimed at

office workers who generally do not need the speed that a verbatim

writer or reporter might need. However, even office dictation, e.g.

letters and reports, has to be verbatim, but a person dictating in

an office will probably speak somewhat more slowly, and with more

pauses, than someone

speaking to other people and not directly to the shorthand writer.

Any writer of Pitman 2000 could

benefit from the shorter forms of New Era if they wish to seek out

and adopt them. Teachers must give the theory as it stands, and

students may be marked on their outlines in exams, but outside of

that, writers are free to adopt any forms they find useful,

preferably after learning the entire system and with a reasonable

amount of experience

of real-life shorthand writing as well. New Era and 2000 writers

alike can benefit from the advanced outlines and phrases offered in

books by high speed writers. Books on other shorthand systems can

often yield useful pointers on abbreviating principles and study

methods.

Top of page

|