|

Sounds/syllables/words omitted from a phrase are underlined

The advantage of phrasing

The advantage of phrasing

A phrase in speech or longhand means a group of

words that belong together, acting as one unit. I have referred to

these throughout as "word groupings" for clarity. Phrasing

in shorthand is often referred to "phraseography" which simply means "writing

phrases" and the shorthand outline for the phrase is called a

"phraseogram".

A phrase in shorthand is the joining of two or more outlines

into one outline. The purpose of shorthand phrasing is to:

-

Gain speed. A

pen lift is equivalent to writing a stroke – the pen has to

travel between the end of one outline and the beginning of the

next outline, and there is inevitably a slight slowing as one

repositions the nib to start the next outline. It is the same as

the difference between writing longhand in separate "printed" letters and

writing in joined-up/cursive letters. Further speed is

gained when obvious words are omitted or when some outlines can

be written in an even briefer form.

-

Improve legibility,

as common word groupings are kept together, and they can be

recognised as a whole. The most useful shorthand phrases are

those which reflect the natural groupings of words.

-

A few phrases are

written with strokes in proximity, or intersected and these save

time by their greater abbreviating potential, rather than

avoiding a pen lift.

CONTENTS

Intro

A phrase is

generally one

continuous outline, occasionally it may be two parts written in proximity or two

parts overlaid

(intersected):

it would be, in the

beginning, at your convenience

The joining of outlines

in a phrase follows the same rules as the formation of normal

outlines – the joins must form legible angles. Some outlines may

change their form for greater brevity, to prevent straggling or make

a join possible:

appear,

it appears that, it would appear, it would, they would

All instruction books

introduce simple phrasing as each part of the theory is presented.

In a very short time the phrases are instantly recognisable and it would seem strange and unreasonable to write the

outlines separately. They are easy to read because they

are mostly groups of short forms and so do not get confused with normal

single-word outlines and, because they are the most common words, they become familiar very

quickly with constant use.

It would be helpful to reread your

instruction book with the specific purpose of searching out all the

phrases they offer (both in the theory explanations and the reading

passages), which may have become somewhat neglected in the haste to

get to the end of the theory. Having gained full familiarity with

shorthand theory, you will find it much easier to revise the

phrasing and use it more in your shorthand writing. This will also

give you a good foundation for your own phrasing and help you avoid

the learner's pitfall of creating overlong or

unhelpful phrases.

Phrasing was not used in the

very early days

of shorthand, but once its possibilities were discovered, it quickly

became the norm and hundreds of high-speed writers over the years

have tried, tested and contributed to the stock of phrases available

today in the various shorthand books.

Phrasing is an

opportunity rather than a rule, and the writer is free to choose

which to use and when. The examples illustrate the general principles

which, once studied and understood, can be applied to produce many

more combinations. Good phrasing is a big contributor to

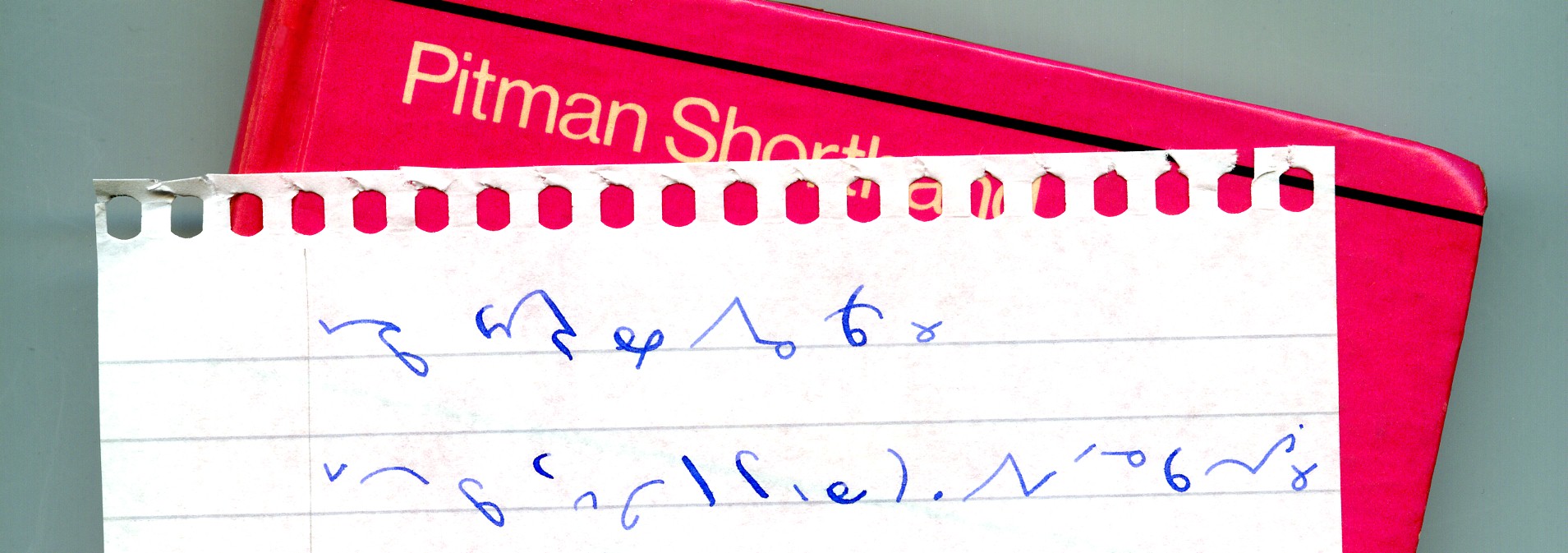

gaining speed, as well as improving legibility – try copying the following

sentences, written with and without phrasing, to instantly experience

the difference good phrasing can make to the flow and speed of

writing:

I am

pleased that you will be able to send us the report and accounts

this morning.

You might try timing a whole page of each of the

above sentences, to see the difference phrasing makes to speed.

There are many

thousands of good basic phrasing opportunities to help you on the

way to high speed, without resorting to overlong or unnatural ones.

Total familiarity with phrases consisting of short forms and simple parts of speech will

bring the hoped-for improvement in speed, and there are enough of

them to keep the learner constantly occupied, well into the

mid-hundreds in speed.

Top of page

Four rules of good phrasing:

1. Words must belong

together. Even if certain outlines would seem to join well, don't

phrase them if they

don't belong together, or if there is a slight pause anywhere.

2. Outlines must join

well. If no good join can be made, don't phrase.

3. The phrase must be

easy to read back. If it is ambiguous or looks too much like another

outline, then it should not be used. Sometimes inserting a vowel

will overcome this.

4. Phrases should not

be overlong. Two or three joined outlines is a good average to work

with, with four or five as a general maximum, although the words

represented by the phrase may amount to more if there are omissions.

The longest phrases would have to be made up of very common short words, if the phrase is to remain legible:

-

In an overlong

phrase, there is a greater

danger of missing any variations that the speaker might make.

The longer the phrase, the less likely it is that you will come

across it exactly as you have practised it. You cannot afford to

wait until a long group of words has been spoken before you

start writing.

-

A very long phrase

lacks legibility. A really long group of words that you are

dealing with regularly and that never varies is a good

opportunity for more extreme abbreviation, but such compressed

phrases should not

be used by the learner or in exams – outside of a particular

field of work or interest, the frequency would be very low, and

hesitating over a

half-remembered phrase loses more time than it was supposed to

save.

-

Your hand may need

to move along the paper before the phrase is completed

– the wrist or little finger that is resting on the paper is best moved

along between outlines and you cannot do this if you are

attempting an overlong phrase. Although you write long

"outlines" in longhand, these are not being done at speed.

Normal handwriting often introduces breaks within a word, for the same reason,

to

reposition the hand.

The ideal is: lots of

short phrases in succession for the most common word groupings. This

will keep the shorthand flowing, legible and not straggling to the lines

above or below.

Variations

There are many

variations on common word groupings, and a textbook phrase that

you have learned may

differ from what was actually said. Once you are familiar with a

particular phrase, you tend to hear (and write) that phrase to the

exclusion of slight variations on it. Such an error will be

undetectable and only come to light when it causes a problem,

embarrassment or a lost exam mark. Alertness is the only safeguard

against this.

For this reason,

phrases should be practised in as many different combinations as

possible. This will reduce hesitations and leave you free to pay

closer attention to the exact words being used. It also provides excellent

intensive practice on short forms, which are the main source of

phrasing material.

Top of page

Which phrases to

learn

Every type of phrasing

opportunity has been described in this section. It is up to you to

choose those that are going to help you. Best results will be

achieved by concentrating your efforts

on simple phrases using the commonest words, not specific to any subject. Opportunities to use them will occur in every dictation you

take. Your time savings are therefore greatly multiplied and you are

able to increase your speed, neatness and accuracy.

The most useful and

frequently occurring phrasing opportunities are the simple ones,

joined end-to-end without any change in the outlines. In these

sections, the other types of phrases have more numerous examples,

simply because they need to be described and illustrated, not

because they are more frequent.

Beginners should resist

the urge to adopt every example indiscriminately,

in the hopes of instant speed improvement. If you are struggling

to recall an advanced or obscure

phrase, this can lose you more time than you hoped to save, possibly resulting the loss of the next few

words as well. The time to consider adopting those is when you are fluent in

the simpler phrases and also in lines of work/interest where they are

occurring regularly. If you pick out your favourites and compile a "to learn" list in

your shorthand resource file, you can review, revise and build upon them

in a controlled manner.

Extreme abbreviation in

phrasing should never be

resorted to through failure to learn the main outlines thoroughly.

Top of page

Lagging behind the

speaker

Some writers advocate

staying behind the speaker in order to take advantage of phrasing. Learners already have the struggle of keeping up,

without deliberately putting themselves further behind the speaker. The speaker could suddenly speed up or, just as alarming, come

out with a string of "impossible" technical words. You

would then get even further behind, with little chance of catching up.

How far you are behind the speaker will settle itself naturally

with your level of skill compared with the speed of delivery and the

difficulty or otherwise of the subject-matter. As a phrase would

seldom be more than five words, that would seem to be the most that

would be necessary to take advantage of all phrasing opportunities.

However, you don't have to hear the whole phrase before you start

writing it.

If you can make or find

dictations that are

comfortably slow for you, then as you write with an even and steady

flow, you will be sometimes with the speaker and sometimes slightly

behind. This is the best position to be in, as your shorthand will

be neat and legible, your writing experience pleasant and free from

anxiety, and you will be relaxed enough to deal within any sudden

increase in the speed, or challenging outlines. Such slow exercises are a good way to practise

this even writing rhythm, and are just as helpful as the

speed-pushing dictations. They are a good corrective against the

erratic "stop-start" writing that can sometimes beset the learner,

especially in the early stages, and give a taste of the

ideal writing experience that will

be achieved in due

course.

It also helps your

posture, as relaxed writing does not need you to hunch yourself

desperately over the notepad to capture those elusive outlines.

Going from one flustered writing experience to the

next without respite is no way to maintain enthusiasm. Recording passages from your instruction book is the easiest

way to produce such practice material, as the correct shorthand is

already there for you to consult beforehand. If you leave them untimed, you

won't get caught up in the "numbers game" whilst you are

doing them. When they feel intolerably slow, you will know it is

time to produce faster ones.

A speaker may say half of what is "obviously"

the start of a phrase, then pause. In such a case you should write

what has been said so far, and forgo that particular phrasing

opportunity. If you don't write down the words dictated before the

pause, you may find that, even within a few seconds, you have forgotten exactly what they were,

when the speaker decides to continue. Any situation where you are

"hoping" for a favourite phrase to be completed is one that reduces

your concentration on the exact words being spoken.

Sometimes when the

speaker resumes after the pause, he/she may finish the phrase, but by

then you will have already written part of it in normal separate

outlines. It is a waste of time, effort and ink to cross these out and replace with the

textbook phrase, when you could be writing the next few outlines. Accuracy is the aim, not

phrase-counting.

Red Paint Pot

Syndrome

When you have a pot of

red paint, bright and shiny, you may be tempted to go round looking for

things to paint red and only stop when the pot is empty or

everything in sight is red. Don't do this with phrasing. Phrasing is

a pot of grease – spread it around to get things moving faster, but too

much in the wrong places will cause slip-ups and regrets!

Top of page

|